Rizal’s Loves: An Analyzed View

by: Dr. Penélope V. Flores

The last time I counted, Rizal had nine loves. But was it really? I consider only three. There are apocryphal stories of Rizal’s girlfriends. However, I don’t believe what our textbooks say about them, and I’ll tell you why.

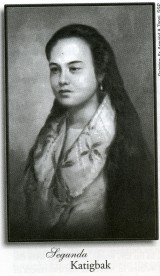

Rizal’s supposedly first love, Segunda Katigbak, was never a love match, but a harmless coquetry of a 14-year-old convent-bred girl and a teen-aged Rizal. Segunda was already betrothed to a Mr. Manuel Luz of Lipa, Batangas when they met. Rizal, then 17 years old, had a teen-age infatuation, albeit the beginning awareness of the other gender. In fact, this was the first time Rizal had a tete-a-tete alone with a girl outside of his sisters. Remember when you were 17 and you kept walking to and fro in front of the house of your Crush? Well then, avoid making it a big love. Nothing more, nothing less.

Leonor Valenzuela, age 14, was a contrived love story made up by his gossip friend, Jose Cecilio (Chenggoy), who derived pleasure in titillating Rizal. He reports to Rizal (then studying in Madrid) of a rivalry for his affection between the two: Leonor Valenzuela (Orang) and Leonor Rivera (the landlady–she was the daughter of Rizal’s former Ateneo landlord and uncle, Antonio Rivera). Rizal was 18 years old. He had no real love for Orang, just a wandering eye syndrome of a Bagong Tao, na nag-bi-binata. Thus, count Orang out.

1878-1890. Third Love: Leonor Rivera, age 15, a Long-distance idealized doomed Love.

Rizal was 18 going 21 and was devoted to her but Rizal just then was opening his eyes to Europe’s Enlightenment where the women are pleasing and the men are gallant. Rizal really was in love with Leonor Rivera. He even invented a code alphabet so that they could write sweet nothings to each other. But soon, Leonor faded into a memory. Why? Because José Rizal was never the preferred choice of Leonor Rivera’s mother, who confiscated all the correspondences between Leonor and Rizal till it frittered down to zero.

In Europe, Rizal conveniently romanced other girls, and forgot he was engaged to her. Eventually the Leonor Rivera-Rizal engagement did not survive a long-distance romance. In the end, it turned into an idealized one (reflected as Maria Clara in Rizal’s Novel, Noli me Tangere), a painful love match doomed to fail from the very start.

Yes, tally this as a Rizal real love. As an engaged couple, they showed real warm affection for each other while it lasted.

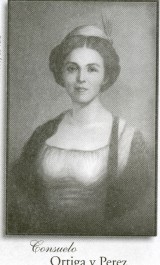

1884. Fourth Love: Consuelo Ortiga y Reyes, age 18, the Madrid flirt, a pleasurable connection.

In Madrid, Rizal courted Consuelo Ortiga, age 18, the daughter of Señor Pablo Ortiga y Rey who was once mayor of Manila and who owned the apartment where the Circulo Hispano Filipino met regularly. Rizal, age 23, was then acquiring and developing his charming ways with women. He treated them with special consideration and with such gallant courteousness. All the young Filipino expatriates courted Consuelo, and she in turn encouraged every one including José Rizal, Eduardo Lete, the Paterno brothers, (Pedro, Antonio, Maximino) Julio Llorente, Evangelista, Evaristo Esguerra, Fernando Canon and others.

Rizal presented Consuelo with gifts: sinamay cloth, embroidered piña handkerchiefs, chinelas– all ordered through his sisters in Calamba (see his letters). Consuelo accepted all the swains’ regalos. Consuelo played Eduardo Lete against José Rizal, and she finally rejected Rizal’s attention in favor of Eduardo, a Filipino Spanish mestizo from Leyte, who a year later, dumped her.

Two-timing Consuelo didn’t really catch Rizal’s true love fancy. Rizal had just impulsively joined the surging crowd. Sorry, about that.

This relationship is what I would call Rizal’s Great Love, in bold capital letters.

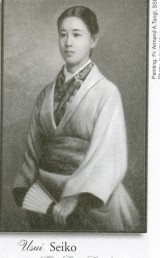

Rizal, age 27, now, an author and a doctor returned to the Philippines in 1887, but because of his Noli me Tangere novel, he incurred the wrath of the Spanish authorities. He had to leave in 1888 where he took the route via Japan to the US and then Europe. In Japan, he met a Samurai’s daughter. They went to excursions and places together. She taught him the Japanese language and its culture.

Remember, Rizal had already been exposed in Germany of the ethnographers, (Fedor Jagor who studied the Igorots) scientists (Dr. Rudolf Virchow, linguist who studied the “Mangianes” of Mindoro), naturalist (Dr. Adolf B. Meyer who collected Mindanao specimen) and anthropologist/historian/Filipinist (Ferdinand Blumentritt).Rizal, now a self-confident mature gentleman-scientist, was attracted by the Japanese culture and immersed himself in its ancient tradition.

What if Rizal unconsciously (he never planned it) entered into a Treaty-port marriage, which had existed for centuries as early as 1630? One month treaty-port marriages were common, especially in Nagasaki. They cost $4 for a license plus $15-$25 for a house and $10 for a servant.

What if Rizal and O-Sei-San, for the whole month in Yokohama, got into this cultural arrangement? There is no mention of this kind in any of Rizal’s biographies. Why? Because the Samurai cultural practice of “temporary marriages” has mainly been shielded away from the lenses of others, much less the “Victorian staid and proper Westerners.” However, this is an ancient respectable Japanese tradition. The women are neither geishas nor prostitutes. They belong to the top of the social class: the Samurai’s daughters!

What if this relationship develops between a highly cultured Samurai daughter and Rizal?

What if, in Rizal’s house on a hill that had paper walls and a splendid view of Yokohama harbor, they write sentimental haiku poetry together?

What if they painted Japanese art? In fact, we have several Japanese art made by Rizal kept at the Rizal Historical Commission collection.

What if they admired the different Japanese temple architectures like Meguro amid Japanese gardens?

What if the rituals of the Tea Ceremony “a cultural event never duplicated, but always imbibed in its peaceful and tranquil meditative aspect” bonded their hearts together in a “floating world”?

What if the Samurai code of loyalty, love of nature’s simple beauty, and options for self-effacement in cultural arts and self-improvement in the art of war, formally made Rizal enjoy his month-long affection for O Sei San?

What if it was a unique love experience with O Sei-San without the hypocritical accompanying guilt and unburdened with embarrassment?

What if Rizal enjoyed this kind of pure carnal love because of its simplicity and honesty? One only has to read Rizal’s journal [1] to intuit the answer.

“O Sei San, sayonara, sayonara! ….No woman like you has ever loved me. …Like the flower of the chodji that falls from the stem whole and fresh without stripping leaves or withering …you have not lost your purity nor have the delicate petals of your innocence faded–sayonara, sayonara.

…I have thought of you and that image lives in my memory…. I’ll always think of you—When shall I return to that divine afternoon…your name lives in the sighs of my lips and your image accompanies and animates my thoughts….When will the sweet hours I passed with you return? When will I find them sweeter, more tranquil, more pleasing…its freshness, its elegance…? Sayonara, sayonara.”

You be the judge. I think he was emotionally awakened and culturally inspired. But I’m treading on dangerous grounds. I know I’ll be mercilessly crucified if I’m not careful. For me, however, it’s a suggestion couched in nested research conjectures characterizing enamored passionate love. Doubtful perhaps but not truly improbable.

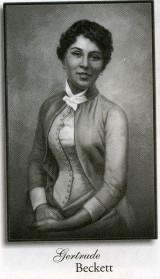

This time on house number 37 Chalcot Crescent, London it was an innocent and open pastime, not real love. Rizal, age 27, had been thrown among his landlord’s daughters– Gertrude (Tottie) and Sissie. When Tottie showed signs of ardor and love, and when Rizal felt being slowly drawn to her, he left her high and dry without notice and without answering her yearning letters. You don’t really do that to a “loved” one.At this time, Rizal was at the British Museum, copying and annotating by hand three hundred pages of Morga’s 1609 Sucesos or History of the Philippines.

In Brussels, Rizal lived in a house of the Jacoby sisters: Marie and Suzanne. Marie Catherine was 55 and Suzanne was 45 years old. Both were besotted by Rizal’s charming manners. A niece named Suzanne Thill lived with the Jacobys during Rizal’s time. Our historians said Aunt Suzanne Jacoby became Rizal’s girl friend. Why would Rizal, age 29, go for a 45 year old, when there’s a young 18 year old who is also enjoying his attentions?There’s a letter signed by a Suzanne saying, in effect—I wear out the soles of my shoes going to the mailbox waiting for a letter from you. Why don’t you write, you naughty boy?In a recent talk at San Francisco Public Library [2], I heard Ambeth Ocampo give explanations of what it really meant…lustful imaginings or “naughty doings” while other historians made it to appear like forbidden love between the two. But hang on…Last summer 2012 in Brussels, my Rizalista friend from Belgium, Lucien Spittael, showed me the Jacoby house where Rizal was a lodger. Rizal’s room was facing the street on the first floor, above the ground floor. There’s a Rizal Historical Marker on that building. Susanne Thill’s room was on the same floor facing the street, next to Rizal’s room. The two aunts occupied the second floor above. The house was a few walking blocks away from the famous fountain, the two-feet tall bronze statue of the Manneken Pis.

I could picture Petite Suzanne and Rizal enjoying each other’s company, walking down that street, sitting in bistros enjoying the passersby, who were admiring and giving judgments of that naked little urchin boy relieving himself in front of a crowd. Then I discovered to my great amusement, that actually, the local name for that beloved cutie is Naughty Boy! Now, let’s suppose it was Rizal and Petite Suzanne (not the elderly Tante Suzanne) who enjoyed each other’s company and used the naughty boy line to recall strolling down the streets of Brussels, wouldn’t that be a personal private little joke between them? Rizal was then waiting for his novel El Filibusterismo in the printing press in nearby Ghent.

A clean fun inspired by an innocent casual toddler’s prank, Little Suzanne and Rizal could possibly and easily have had a healthy boyfriend-girlfriend relationship but it was just that. Clean fun and very tentative, spent under the watchful eyes of two elderly aunts within the same roof, while strolling by the streets, where a naughty boy, (he hasn’t shed his baby fat yet), is shamelessly urinating in public. I suggest that the ubiquitous Filipino sign be posted up saying: Bawal Umihi Dito. Wouldn’t that be a riot for all the visiting Filipino Diaspora crowd!It’s unfortunate that our historians had been side-blinded by the older Suzanne, thus they never got a picture of Little Suzanne. Yes; a very short-lived lovely affectionate experience. No; not a great shattering love affair.

1891. Eighth Love: Nellie Boustead, age 20, the rich heiress. She antedated the modern Pre-Nuptial arrangement. A Love Game. (In tennis Love means player scores no points.)

In Paris, France, Rizal fell in love with Nellie Boustead, a Filipina whose rich father (Filipino-Anglo French) Edward Boustead, owned a villa in Biarritz. Rizal was on the rebound at that time because; he received news that Leonor Rivera, his fiancée, had married Charles Kipping, a British engineer working on the Dagupan railways.

In Paris, France, Rizal fell in love with Nellie Boustead, a Filipina whose rich father (Filipino-Anglo French) Edward Boustead, owned a villa in Biarritz. Rizal was on the rebound at that time because; he received news that Leonor Rivera, his fiancée, had married Charles Kipping, a British engineer working on the Dagupan railways.

Rizal (now free from a romantic engagement) did propose marriage to Nellie. He was anxious to start his own family at age 30. Nellie was a good candidate. The mother was from the Genato family in Manila. Nellie was good at fencing. She was well educated, very intelligent, and good looking.

I would not call it Rizal’s great romance, because right at the Boustead’s villa in Biarritz, from the very start the courtship encountered many complications. First, Antonio Luna thought Nellie was favoring him. Luna and Rizal almost came to a sword duel, but Luna withdrew and gave up the suit. In the end, Nellie, who was a Protestant, gave some marriage conditions that Rizal could not accept (to renounce his Catholic faith and become a Protestant). I would hesitate to call Nellie Boustead Rizal’s great love. It was more a Rizal licking-of-wounds-love-after having been spurned by Leonor Rivera.

I see Nellie Boustead as antedating a modern Pre-Nuptial marriage arrangement. Not a real love, more like a marriage transaction. If it succeeded, Rizal would have become a successful practicing ophthalmologist in Paris and eventfully would have become a Frenchman.

Could we have gotten so demeaningly low to ourselves as a nation to have a naturalized Frenchman as our national hero? Definitely No Love Lost on this one. The possibilities are too staggering to contemplate.

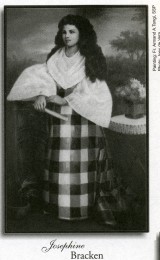

Rizal was already 34 when he met Josephine. She accompanied her stepfather, Mr. George Tauffer of Hong Kong, who sought Rizal’s expertise in Dapitan as an eye doctor. This European woman brought back memories of his European sojourn. At first, Rizal pitied the young Irish girl, and evoked a protective feeling, but the nearness and proximity sparked their love. Remember, Rizal was an exile, deprived of many liberties and conveniences. His future was uncertain. Josephine was there. She was kind, loving, and served Rizal hand and foot. Rizal wrote in his journal that she had fulfilled his needs more than any Filipina girl could ever give him.

Did he sound very lonely and vulnerable? Yes, and did he fall in love? Yes. She served as his dulce amor. They betrothed themselves to each other as husband and wife, not canonically. They planned to marry within the church, but couldn’t. The Archbishop of Cebu demanded that Rizal sign a retraction letter prepared by the diocese. Rizal refused. Josephine conceived a (boy) who, in her last trimester suffered a miscarriage. The infant was named Francisco and Rizal buried his aborted son in Dapitan.

We read Rizal’s letters constantly praising Josephine for her characteristics and attributes. He even begged his sisters to be nice to Josephine. In my view, Josephine Bracken was the dulce extranjera who he loved dearly, of whom he made a sculpted face in bas relief, drew several sketches of her, and before he was executed, dedicated a book that read: To my dear and unhappy wife, Josephine. The book dedication served as a legitimizing testament of his marriage to Josephine in his last hours. But it was a sad ending, as we know on the morning of 30 December 1896.

Yes, I believe Josephine Bracken was José Rizal’s great love, comfort, and joy.

Rizal loved Leonor Rivera with an obligation to a long-distance idealized love that never endured. He was distraught when it ended.

Rizal loved O-Sei-San with a tender ethereal love. He was full of longing and regret when it ended.

In the case of the other women in Europe, he was actually relieved and happy the encounters ended.

While to Josephine Bracken, he finally pledged his troth, with a tragic end.

****